Recuperando Interações da Terra: Apoie o Cinturão Verde Guarani

Aproximadamente 13.000 hectares de Mata Atlântica são desmatados por ano. Há 150 anos, o estado de São Paulo era composto pela Mata Atlântica. Nos últimos cinco anos, 7,2 milhões de quadrados metros (720.000 ha) de Mata Atlântica foram desmatados somente na cidade de São Paulo.(1) Em contrapartida, só em 2019, as comunidades Guarani em São Paulo recuperaram e plantaram mais de 300 espécies de árvores como Pitanga, Cambuci, Araucária, Palmito Juçara.(2) O PL 181/2016: Cinturão Verde Guarani tramita na Câmara Municipal de São Paulo desde 2016.(3) Iniciativas Guarani em São Paulo vem recuperando de solos anteriormente degradados por monoculturas. A tekoa Kalipety, no sul de São Paulo, produz hoje mais de “50 variedades de jety (batata doce), 16 tipos de avaxi (milho), 14 de mandi'o (mandioca), 10 de kumanda (feijão), 11 tipos de abóbora, abacaxi, entre outros.”(4) As plantas e sementes produzidas no tekoa Kalipety são replantadas e compartilhadas com outras comunidades Guarani dentro e fora da área urbana de São Paulo. A recuperação ambiental liderada por iniciativas Guarani beneficia todos os moradores da cidade de São Paulo e seu entorno. O comércio de sementes por meio das redes de mobilidade Guarani e a variedade da agricultura Guarani aumentam a segurança alimentar e a recuperação dos solos e da Mata Atlântica em São Paulo.

Recuperando Solos Degradados

Com sua agricultura tradicional, os Guarani vêm recuperando solos degradados em São Paulo. Combinando métodos ancestrais de agricultura e técnicas recentes de agroecologia e permacultura, estão reflorestando áreas desmatadas, cuidando de mananciais e rios poluídos. Os Guarani, como agenciadores da terra, e com seu conhecimento milenar da Mata Atlântica na área hoje conhecida como São Paulo, aumentam a qualidade ambiental em toda a cidade de São Paulo.

Envolvimentos humanos-não-humanos

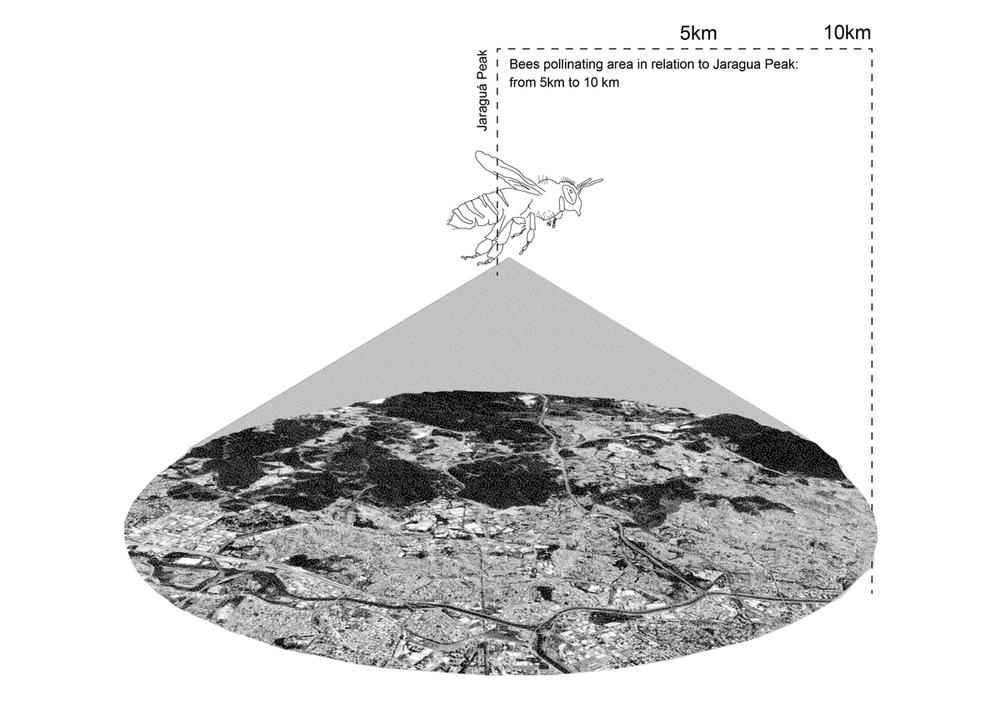

O Cinturão Verde Guarani recria infraestruturas da Mata Atlântica como infraestruturas emaranhadas de cuidados entre multi-espécies. Em uma das tekoas no Jaraguá, a tekoa Ytu, lideranças Guarani estão reconstruindo infraestruturas de abelhas indígenas da Mata Atlântica. Originalmente, mais de 300 espécies de abelhas existiam na floresta, que desapareceram anos atrás, como descreve um dos líderes Guarani do tekoa Ytu.(1) A partir de 2021, 28 colméias e sete espécies diferentes de abelhas sem ferrão, estão sendo criadas e cultivadas em aldeias Guarani do Jaraguá. Em contrapartida, as abelhas criadas no Jaraguá polinizam áreas até 10 km do Pico do Jaraguá.(2)

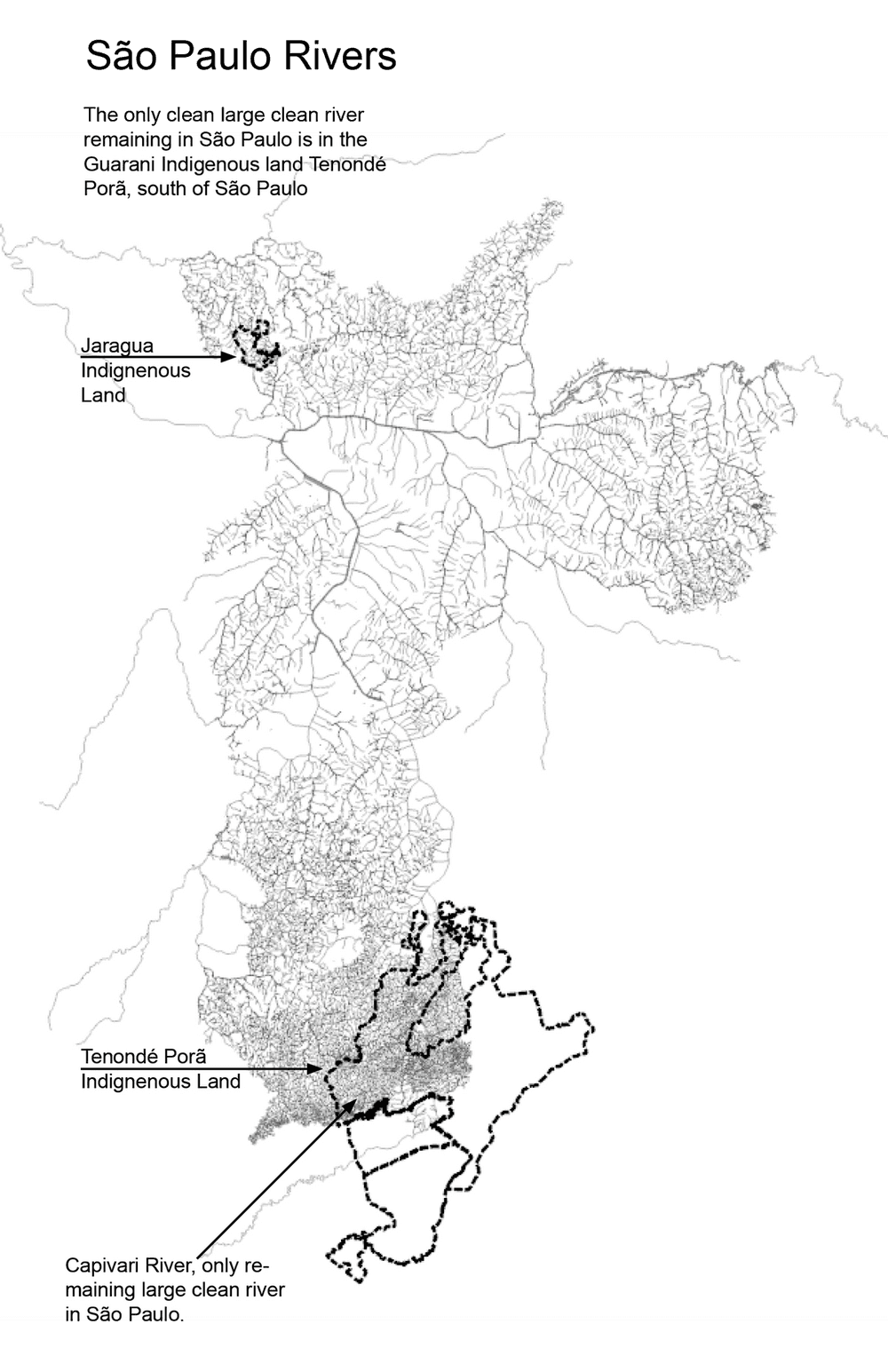

Além disso, o último grande rio limpo de São Paulo está em território Guarani. O Rio Capivari, está situado na Terra Indígena Guarani Tenondé Porã, ao sul de São Paulo. A agricultura guarani e sua disponibilidade de alimentos também trazem de volta aves que antes haviam abandonado a região devido ao desmatamento.

Distância para água potável

Para o Guarani, yy (água) é sagrada. Como um dos podcasts do Cinturão Verde Guarani de abril de 2021 sugere, para os Guarani, o acesso à água potável é essencial para a manutenção do seu modo de vida tradicional.(1) O crescimento urbano no entorno do Pico do Jaraguá aumenta a poluição dos rios. Sistemas incompletos de esgoto doméstico descartam sua poluição no Ribeirão das Lavras, o principal rio que abastece algumas das tekoas Guarani no Jaraguá. Como descreve um líder Guarani, quando era criança, o Ribeirão das Lavras era limpo e dava para nadar e pescar.(2)

Desde a década de 1970, lixo e poluição provenientes do crescimento urbano do entorno drenam para as lagoas e rios na área onde estão os tekoas Guarani. A poluição da água contaminou crianças e adultos. Além disso, a maior parte das tekoas do pico Jaraguá não tem acesso a canos de esgoto. As fossas sépticas fornecidas para as casas muitas vezes inundavam e vazavam, contaminando e restringindo ainda mais as áreas onde residiam as casas Guarani.(3)

O relatório da Funai para a demarcação da Terra Indígena Jaraguá menciona que a empresa gestora de água e resíduos SABESP estava tomando medidas, em parceria com o governo de São Paulo, para melhorar a qualidade da água no Jaraguá. Com a implantação do “Programa Córrego Limpo”, a SABESP tinha planos de ampliar a rede de esgoto. No entanto, ainda enfrenta desafios para consertar o sistema de esgoto da região, desde 2015 as comunidades do Jaraguá, juntamente com aliados não-Indígenas com experiência em construções de permacultura, e com apoio do Programa Aldeias do Centro de Trabalho Indigenista (CTI), vem construindo seus próprios sistemas de esgoto ecológico, adaptado às condições específicas de cada tekoa.(4)

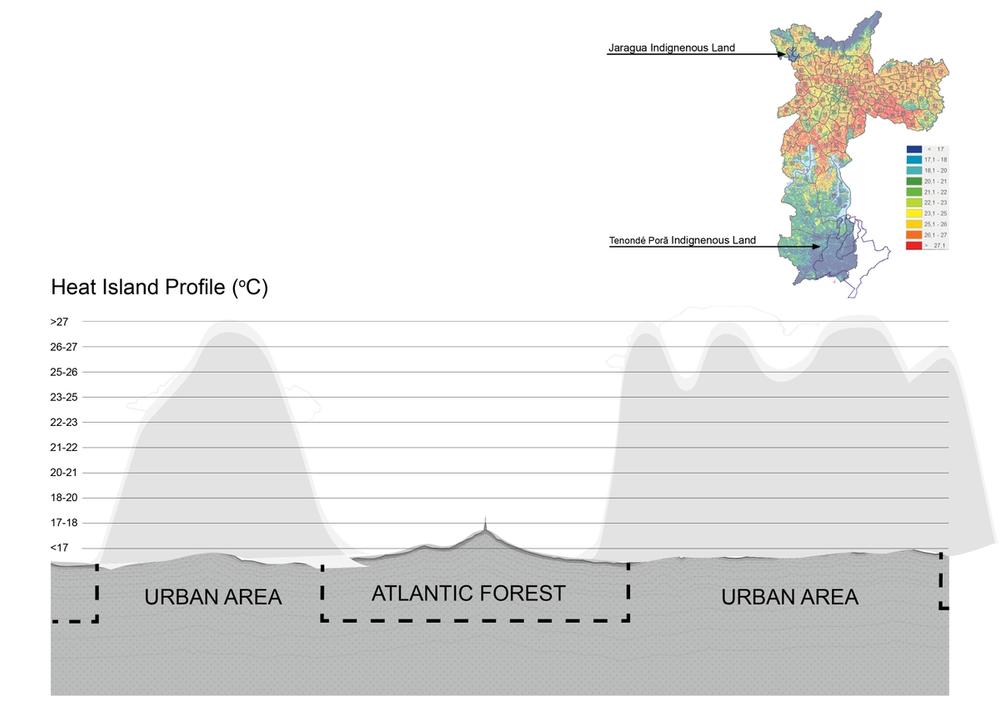

Ilhas de Calor

Um mapa de ilhas de calor de São Paulo revela como as áreas onde existem Terras Indígenas Guarani também apresentam a menor incidência de ilhas de calor na cidade.

O cinturão verde Guarani beneficia todos os moradores de São Paulo, já trabalhando para enfrentar desafios ambientais e climáticos presentes e futuros. É também responsabilidade de todos habitantes não-Indígenas de São Paulo de suportar o Cinturão Verde Guarani.

Recovering Land Interactions,

Reworking São Paulo: Support the Guarani Greenbelt

The Guarani Greenbelt, also known as PL 181/2016, is a law project written by Guarani communities in Sao Paulo, and Jurua city council and deputies allies. The Guarani Greenbelt proposes that Sao Paulo infrastructures become integrated with the Atlantic Forest infrastructures to increase the climate and environmental safety in present and future Sao Paulo. Guarani ongoing initiatives of environmental recuperation in Sao Paulo, such as the recuperation of soils previously degraded by monocultures and the cleaning of polluted rivers, benefit the entire city and its surroundings, while increasing Atlantic Forest preservation.In the last five years, 7.2 million square meters (720,000 ha) of Atlantic Forest were deforested in the city of São Paulo alone. In contrast, in 2019 alone, Guarani communities in Sao Paulo recuperated and planted more than 300 tree species such as Pitanga, Cambuci, Araucária, Palmito Juçara, in the surrounding of the tekoa Yvy Porã in the Jaragua. The trade of seeds between tekoas through Guarani mobility networks have increased both the variety of Guarani food agriculture, increasing food security, while also recuperating soils. As of 2021, the tekoa Kalipety, in the south of Sao Paulo, today produces more than “50 varieties of jety (sweet potato), 16 types of avaxi (corn), 14 of mandi’o (manioc), 10 of kumanda (beans), 11 kinds of pumpkin, pineapple, among others.” The plants and seeds produced in the tekoa Kalipety are replanted and shared with other Guarani communities within and beyond Sao Paulo urban area.

Approximately 13,000 hectares of Atlantic Forest are deforested per year. 150 years ago, the state of São Paulo was composed of Atlantic Forest.

Recovering Degraded Soil

The work of Guarani communities in Sao Paulo is the only reason the Atlantic Forest still exists in São Paulo. With their traditional agriculture, the Guarani have been recuperating degraded soils in São Paulo. Combining their traditional agriculture methods and recent techniques such as agro-ecology and permaculture, the Guarani are reforesting deforested areas, taking care of polluted water fountains and rivers. The Guarani as land stewards, who have been stewarding the lands underneath Sao Paulo for thousands of years, even after Sao Paulo and Brazilian government stole and land grabbed Guarani and Atlantic Forest inhabitants lands, remain responsible and keep increasing the present and future of environmental security in entire São Paulo.

Multispecies Entanglements

The greenbelt highlights and recreates the Atlantic Forest and Guarani infrastructures as entangled infrastructures of multi-species care. In one of the Jaragua tekoas, the Tekoa Ytu, Guarani communities have been re-constructing Atlantic Forest Indigenous bees’ infrastructures. Originally, more than 300 bee species existed in the forest, but they had disappeared years ago, as one of the Guarani leaders in the tekoa Ytu describes. As of 2021, 28 beehives and seven different species of Indigenous bees, which is what the founders/leaders of the Guarani greenbelt call them, without stung are being raised and cultivated in Guarani villages in the Jaragua.

In return, the bees raised in the Jaragua pollinate areas as far as 5km to 10km from the Jaragua Peak.

In addition, the last large clean river in Sao Paulo is in Guarani territory. The Capivari river, is situated in the Guarani Indigenous Land Tenondé Porã, south of Sao Paulo. The guarani agriculture and their food availability also brings back birds which had abandoned the region previously due to deforestation. Initiatives by Guarani communities in north and south of Sao Paulo are benefiting all of Sao Paulo inhabitants, considering their lives and environmental quality inside and outside their houses.

Distance to Clean Water

For the Guarani yy (water) is sacred. As the title of one of the Guarani Greenbelt podcasts from April 2021 underlie, for the Guarani, access to clean water is essential for Guarani existence. Urban growth in the Jaraguá surroundings has increased the pollution of rivers. Incomplete domestic sewage systems dispose their pollution in the Ribeirão das Lavras, the major river that serves the Guarani Tekoas. As one Guarani leader in the Jaragua communities describe, when he was a children, the river that crosses the tekoa Ytu, Ribeirao das Lavras, was clean and he used to swim there. According to another testimony, in the 1960s the river Ribeirão das Lavras was clean, they used to drink its water, swim, fish, and wash clothes there.

Since the 1970s trash and pollution from surrounding irregular urban growth drains into the ponds and rivers in the area where Guarani tekoas are. The water pollution contaminated children and adults and undermined the Guarani communities’ water source, used by them for fishing, swimming and facilitating their nhanderekó. In addition, the largest part of the tekoas in Jaragua peak don’t have access to sewage pipes. The septic tanks provided for the tekoas often flooded and leaked, contaminating and restricting even more the areas where Guarani houses resided.

The Funai report for the Jaraguá Indigenous land demarcation from 2013 mentions that the water and waste management company SABESP was taking measures, in partnership with the São Paulo government, for improving the water quality in the Jaraguá. With the implementation of the “Programa Córrego Limpo” (clean stream program) SABESP had plans to grow the sewage network. Nonetheless, still facing challenges to fix the sewage system in the area, since 2015 the communities in the Jaragua, together with Jurua allies with experience of permaculture constructions, and support of the Programa Aldeias, have decided to construct their own ecologic sewage systems, with filters that clean the water before giving it back to the ground. Each tekoa in the Jaragua now has its own ecological sewage system adapted for the specific conditions of each tekoa. In the tekoa Ytu, a composting toilet was installed in 2018, and a system called “sceptic filter” substituted common sceptic tanks, without generating common sewage.

The last large clean river in Sao Paulo, the Capivari river, is in Guarani territory. It is situated in the Guarani Indigenous Land Tenondé Porã, south of São Paulo.

Heat Islands

Tellingly, a urban heat map of Sao Paulo reveals how the areas where Guarani Indigenous Lands exist are also the lower incidence of urban heat in the city. Heat islands in Sao Paulo.

The Guarani greenbelt is not a project that would benefit only the Guarani; it is meant to be maintained in collaboration between Guarani and Jurua, to increase life quality and environmental security in entire Sao Paulo, already working to face future challenges such as the rising of climate change.